Clyde Everett Weeks (Sr)

Birth

Death

Spouse

My paternal Grandfather is Clyde Everett Weeks. He died of cancer in September 1979. We called him “Dad”, presumably because my parents did when we were young. He was a handsome man with pure white hair. He had an interesting life. I understand that his father was not particularly ambitious or much of a leader in his home and that my Grandfather left home in Lansing, Michigan when he was relatively young as he lied about his age of 16 in order to join the army. I believe that they let him in because he registered for the draft when he was only 16. He soon found himself in Vladivostok, Siberia, in Russia during World War I. His career in the army continued through World War II.

He was married in 1924 to Bertha Larsen. I never met her, but understand that she was a nurse. My Father has spoken fondly of her, but I really know little about her life, other than the fact that she was my Father’s Mother and that she also had two other children, Sharee and Michael.

This began a second life for my Grandfather. He became assistant manager of the Singer Sewing Machine center in Provo on Center street, where he worked for several years. He soon met Emily Gatiker at the Singer Sewing Center. He repaired her sewing machine. Emily was a lovely woman, who had suffered through a stressful divorce from her first husband, a Mr. Stoddard. Emily came to be known at Aunt Emily. We would often go to visit “Dad & Emily” on Sunday afternoons, during my youth. Emily brought with her four children from her previous marriage. Their names are Myrna, Martin, Karen, and Glen. They also had one daughter, whom they named Jerri Susan. She was a year younger, than I. They lived on about 420 East 200 North in Provo.

Emily worked at BYU in the Alumni Department. One day, she heard that there was an opening in the new BYU Development Fund Department at BYU. My Grandfather applied for the job and got became BYU’s Assistant Development Director. He ultimately ended up working there until his retirement. His responsibilities included negotiating with people and arranging for bequeathments and donations to the university. I remember going to his office in the administration building at the university, when I was a young man, to visit him. It seemed like a very nice place to work.

He seemed to be very highly respected and enjoyed his work. He had beautiful handwriting. I remember, that every birthday, I would receive a special birthday card from him with a crisp $1 dollar bill. I always looked forward to this kind thought.

My Father’s Father grew up in Lansing, Michigan. The Weeks family originated in England. Originally, I understand that the name was Wicks. It is supposed to have changed after these people migrated to America. Perhaps it changed even before this. I guess I can check this out in my genealogy, which I will include at the end of this history.

My Father’s Mother, Bertha Larsen grew up in Canada. Her family was from Denmark. She had two brothers named Grant and Wilford. There may have been other brothers but I don’t remember any sisters. I know little about her other than that she was a nurse and that she died of cancer when my Father was 16 years old.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

First Interview of Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr.

Second Interview of Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr.

Third Interview of Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr.

Fourth Interview of Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr.

Fifth Interview of Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr.

His Life Story

My Birth & Early Life

On September 3, 1902, a baby boy was born to George

Clarence Weeks and Sarah Maude Jenkins at La Crosse, La Porte, Indiana.

Two other children preceded him in this family, namely Owen Royal Weeks,

Born November 25, 1897 and Pearl Emily Weeks, born October 4, 1900.

This baby boy was me. I was told that father worked

on the railroad in La Crosse. When I was two the family moved to 6th

Street in Ashland, Ohio where father worked for the Myers Pump Company

which manufactured water pumps. Sixth Street ran into Orange and when I

was old enough, I went to grammar school in the Orange Street School. I

remember my third and fourth grade teachers who were twins. I thought

them very beautiful. They were always nice to me and I imagined I was in

love with them.

About this time we moved to Lansing, Michigan. On

arriving there we moved in with Uncle Willie (Wilbur) and Aunt Sarah

Weeks until we could find a home to rent. Dad began working for the Reo

Motor Car Company in the machine shop. Uncle Willie worked as an

automobile painter for this same company. We were soon able to rent a

house on Hillsdale Street, near the corner or River Street. While living

here my younger brother, Frederick Hall Weeks, was born on September 12,

1913. He was named after Fred Houghton whose wife was Nellie Hall.

Nellie was mother's cousin. They lived in Ohio. Second cousin, Fred, was

only about 15 years older than I.

We had a burn out in the home on Hillsdale Street

and moved into the house next door which faced River Street. While

living in this house, the river burst its banks and flooded our basement

and about a foot into the main floor. These two disasters were very hard

on my parents.

When I was about in the 6th grade, Grandfather

Weeks died and left dad $800 which was used for a down payment on a

house on Monroe Street, not far from Uncle Willie's home. This was the

last home I lived in with my family.

I really never had much childhood and virtually no

adolescence. Thus I never learned to swim or play ball or do any of the

things boys usually do during their "growing up" years. Even while in

Ohio I delivered washing and ironing in my little wagon which my mother

did for other people. Almost every day I had to go along the railroad

track to look for lumps of coal which had fallen from the overly loaded

coal cars so that we would have fuel for cooking and heating our house.

In Lansing I delivered newspapers

for the Lansing State Journal in the evening after

school and in the morning before school I worked in a nearby milk

bottling plant. All of my earnings had to be given to my mother;

however, I would often manage to get a few extra papers to sell on the

street.

This money I kept and would occasionally afford a

treat. My favorites were those chocolate-coated cookies with

marshmallows on top.

My mother was a harsh disciplinarian. During my

early years she often beat me with a switch which she made me get for

her. I was required to go to my room to wait for her to come to whip me.

I never fought back but learned to notch the switch so that it would

break easily. I can't remember my parents ever giving me one cent but if

I was caught withholding any money I had earned, a beating resulted.

Father never whipped me; a cuff to the side of the head was all I ever

got from him.

Much against my will, my parents took me out of

school before I finished the 7th grade because they needed the income I

could make in order to support the family. I was always tall for my age

and could pass for quite a bit older than my years. My first full time

job was as messenger at the Reo Motor Car Company where I ran errands

delivering messages between the various departments of the plant. I

bought my lunch at the plant while working there and these were the best

meals I had ever eaten. It was while working here that I was befriended

by John Leonard who was a year or two older than I. He was not the best

influence on me because it was then that I began smoking without my

parents knowing it. I was just trying to be manly like the rest of the

fellows.

Dad was still working in the Reo machine shop when

I found a better paying job with an auto parts company that made motor

blocks for cars. I operated a drill press which bored numerous holes in

the block at one time. My main problem was that I couldn't get the hang

of sharpening the drills properly. I tried so hard but they burned

rather than drilled so I didn't last long there.

My brother, Owen, was a motorman for the streetcar

company and he got me on as a conductor. The motorman sometimes let me

operate the streetcar and on one occasion while the motorman was at the

rear of the streetcar I rammed right into the back of the car ahead of

me. I was frightened and knew that I was finished with that job, so in

the morning I went to the office and turned in my badge--I quit before I

was fired.

World War I was on and I wanted to get into the

action. My parents would not give their consent but I enlisted in the

Navy anyway and was sent to Chicago by them for induction and final

physical. Naturally, I had to fib about my age. I felt real smug about

getting past this hurdle but when I had my physical the doctor decided I

didn't have enough pubic hair (I was only 15) and sent me back home to

grow up.

After this experience I enrolled in a telephone

installation course with the Western Electric Company. They sent me to

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where I spent the winter in school and learned

the inner workings of the telephone exchange. This was a rather tender

age to be alone and so far from home. After graduating from this, I

returned to Lansing but had a disagreement with my parents when they

tried to restrict my comings and goings and probably my smoking too

which I now did openly. I rented a room about two blocks from home and

never lived at home with my parents again. Mother and Dad were having

marital problems and one day Dad brought his suitcase and moved in with

me for a while. I was working for the Bell Telephone System at this

time, but not long afterward the telephone workmen went on strike so I

was again out of work.

I was never without work for long. Next I began

working for the Fisher Autobody Company. They had a contract with the

government making oak wheels for cannons. I would putty all the holes

and cracks on the wooden spokes and sand them to get them ready for

dipping into the paint. These were for the war effort.

June 6, 1919

Early Military Career

The 18 to 45-Year-old men had to sign up for the

draft as World War I was still on and men were desperately needed. At

various places in town women would be set up to register men for this

purpose, so I marched in and registered using May 12, 1900, as my birth

date. They gave me my coveted draft card without requiring a proof of

birth. With the draft card in hand I went to the Army Recruiting station

and was accepted as an enlistee and sworn in on the spot.

In the early summer of 1919 (I was not yet 17 years

old) I was sent to Columbus, Ohio to boot camp.

Little is known by the general public of the story

of America’s Adventure in Siberia 1918-1920. There were no radio and

television and the press gave only meager publicity to the American

Expedition in Siberia. Only a few troops were involved so it was not

generally known that the United States participated in this action. War

did not cease in this area with the signing of the Armistice in 1918.

World War I did not finally terminate until peace was signed in 1921.

All participants in the American Expedition in Siberia are recognized

veterans of World War I and were awarded the Victory Medal with the

Siberian Clasp. I was awarded this medal.

Major General William S. Graves, U.S. Army,

commanded the expedition. This was a combined allied military campaign

to North Russia and Siberia and the troops in Siberia consisted of

contingents of English, Japanese, Chinese, French, Czech and American

units. Major General Graves wrote a book covering this unusual campaign

titled

America's

Siberian Adventure (BYU Library 940.43.G 78). To set the

stage for a recital of my little part as one of the troops who spent a

winter in this cold, uninviting land, I quote a few excerpts from his

book.

"Siberia was inhabited in part by semi-civilized

natives and in part by political exiles and there were now added great

bodies of liberated prisoners of war I seemed to be the only military

representative who was aware that we had a war of our own in Russia and

that our war was independent and separate from the war in France. The

Armistice had absolutely no effect in Siberia.

"The principle of non-interference in Russian

affairs limited the activities of the American Forces in Siberia to

guarding supplies and keeping lines of communication open… People in the

United States can have no conception of the conditions in Eastern

Siberia where there is no law except the law of the jungle which the

Japanese and Kolchak supporters were using and the Americans could not

use.

"Admiral Kolchak, who represented the Czarist

regime, and who the United States supported with arms and ammunition and

clothing, was defeated by the Bolsheviks. He was tried by the Bolshevik

military court and was shot February 7, 1920."

General Graves in his summation said 'I was in

command of the United States troops sent to Siberia and I must admit, I

do not know 'what the United States "was trying to accomplish by

military intervention....The Siberian expedition has been a great

fiasco, for which the allied nations must be blamed. It was a great

mistake to send any expedition at all.

American intervention in Siberia was a fruitless,

dismal tragedy, comedy.

Secretary of War Newton D. Baker said, "I cannot

close this foreword without expressing the gratitude of our common

country to those soldiers who uncomplainingly and bravely bore in that

remote and mystifying place, their part of their country's burden. Those

who took part in it can have the satisfaction of knowing that the

American force in Siberia bore itself humanely and bravely under the

orders of a commander who lived up to the high purpose which led their

country to establish a stabilizing and helpful influence in remote

wastes inhabited by confused and pitiful people. They too, 'I think,

have the reassurance that if there was a defect of affirmative

achievement, history will find benefits from the negative results of

American participation in Siberia; things that might have happened, had

there been no American soldiers in the Allied force, but which did not

happen because they were there, which would have complicated the whole

Russian problem and affected seriously the future peace of the world.

MY LITTLE

STORY

During World War I I was caught up in the

excitement of the war and I developed a desire to enlist in the service

and get into the action. I was too young to enlist even though I tried.

One day, when I was about 15 years of age in 1917, I presented myself to

the Naval

Recruiting Officer and applied for enlistment. I

fibbed about my age and they didn't require any proof of age so I was

accepted for service in the Navy. I guess they were pretty hard pressed

for men. I was issued a transportation request and some money for food

and lodging and was put on a train for Chicago. I arrived in Chicago

real pleased with myself for my deception and thought I was on my way to

the Navy. The very next day I was sent to a Doctor for a final physical

examination. He looked me over and told me that I was a bit immature for

a lad of l8 and said that I had better return home and wait until I was

old enough to enlist, whereupon I was issued a train ticket and sent

back to Lansing a very disappointed young man.

Failing to get into the service, I decided to

enroll for a course in telephony with the Western Electric Company. They

sent me to Pittsburg, Pennsylvania where I attended a six months course

and learned the art of terminals in a telephone office as well as

installation of telephones in homes, so the winter of 1918 was spent in

Pittsburg. Upon the conclusion of the course I returned to Lansing,

Michigan and went to work for the Bell Telephone Company, where I worked

for a few months when the workers went out on strike and I was without a

job or source of income. I still had a yen for getting into the service

and asked my parents consent which required them to sign a waiver job or

source of income. I still had a yen for getting into the service and

asked my parents consent which required them to sign a waiver on my age.

They, of course, refused. The War was going strong

in Europe and men were needed. The government issued orders that all

males between the ages of 18 and 45 were required to register for the

draft. I had watched the ladies who were registering men for the draft

and it looked like a very easy procedure so decided to go in to the

registration station and tell them that I was 18. I chose a birthday,

May 2, 1900, which would make me old enough. I went in and registered

with no questions asked. I now had a draft card. Later on I decided to

try to enlist in the Army and went to a recruiting station and applied

for enlistment. I again fibbed about my age, using the new birth date

that I had used. The officials asked me for my proof of age and I handed

them my draft card which they accepted as proof of age without question

and I was sworn in as a Private U.S. Army. The draft card did the trick.

At that time I was 16, going on 17.

I chose the U .S. Cavalry for service on the

Mexican border and was sent to Columbus, Ohio for boot camp training. I

went through some body building and rigorous training for a short time

and was preparing for small arms and field training and indoctrination.

One morning when our group was in the large recreation hall engaging in

calisthenics, a Major came in and called us all to attention and made

the announcement that there was urgent need for a number of men to be

sent to a theater of operations in Siberia and asked if there were any

men in the group who would be willing to transfer to the Infantry and go

to Siberia. I had little idea where Siberia was but I knew it was a long

ways away and that there was still someplace where fighting was going

on. With little thought of the ultimate consequences, I stepped forward

and volunteered. I wanted to get where the action was. A few other

fellows, perhaps 20, joined the group.

We were processed for departure and in a couple of

days were put on a train enroute to San Francisco. Upon arriving there

we were put aboard a ferry boat, the General McDowell (see pictures),

and were taken to Fort McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. We

remained there for a short time and then boarded the U.S. Army Transport

THOMAS (see picture) for the journey to Siberia, I have no record of the

exact date of departure. We stopped in the Hawaiian Islands to replenish

the ship's fuel which took two or three days. A lovely lady, Mrs. Oggs,

came down to the ship and got permission from the commanding officer to

invite a few fellows to be her guests at her lovely home on Mt.

Tantaless. Out of all the troops there she picked only four of us and I

was one of the lucky ones. She took us to her home and served us a

lovely dinner after which she took us on a tour of the area in her Model

T Ford. (See pictures). From there we took the Northern Circle route to

Vladivostok, Siberia. This was a lot of excitement for a kid my age and

I enjoyed it all.

I was assigned to Headquarters Company, 3lst U.S.

Infantry, the main body of which was stationed just outside the city. We

were marched from the ship to an old stone barracks (See picture) a few

miles from town. The building had no water or sewage facilities. All

water had to be hauled in, in small tank carts pulled by mules. (See

pictures) The building was cold and damp. The only heat came from a few

fire places built into the walls of the building. They did not heat it

but they did provide a place for us to huddle around and get a little

relief from the cold. The Army somehow provided us with some coal,

probably robbed from one of the ships.

There were some old iron frames in the building

which we converted into bunks. I remember that when I arrived tired and

pooped at the end of a long journey, I was handed a pair of pliers and a

mattress cover and was told to go outside and get some wire off some

bales of straw and to fashion me a bed by stretching the wires across

the iron frames to form a support for my mattress, which consisted of

the mattress cover filled with straw. There were no latrines in the

barracks so we dug open air ones outside. They sure were some fancy

tenholers; enclosed around the sides with canvas strips, "but without

roofs. It was quite an experience to use them in frigid and inclement

weather. Some Chinese coolies came around once a week and collected the

accumulation and trotted away with it in cans attached to the ends of a

pole which they carried over their shoulder. They undoubtedly were using

it for fertilizer.

We, of course, had no way of bathing in the

barracks, so about every week or ten days we were marched down to an

area where makeshift showers were operated. Upon arrival at the showers

we were obliged to strip down and turn our clothing over to the German

prisoner attendants who put them through a hot steam delousing machine.

When the clothing was returned to us, it was, of course, shrunken and

terribly wrinkled. On entering the makeshift shower the German prisoners

operating them smeared our bodies with a slimy, yellow soap mixed with

kerosene which was supposed to control lice. The showers consisted of

barrels with an opening in the bottom. The prisoners poured tepid water

into the barrels and let it drizzle down over us. Water was very scarce,

so we usually emerged pretty slimy and sticky. Most of us soon arranged

to get a bath elsewhere, usually some generous Peruski ladies with whom

we made friends.

We also learned to hide a good uniform under our

bed sacks and prevent them going through the delouser. We wanted to look

sharp when we went to town. I had no training in the use of weapons

before arrival in Siberia, nonetheless I was issued a 30.06 Springfield

rifle completely covered with cosmolene and a bayonet, one belt of

ammunition plus two extra bandoleers of ammunition and four hand

grenades. I was placed on the guard roster and assigned to guard duty

before I had fired my weapon or tossed a grenade. I felt a little

overwhelmed by all of this, however, I did have an opportunity to learn

my weapon, toss grenades and engage in bayonet practice between guard

assignments. I also learned how to march properly and stand tall. I

shall always be grateful to Corporal Joyner, our drill master, for

kicking me in the rump when I had a tendency to slump or bend my knees.

He really made me shape up.

Not long after I arrived in Siberia I was assigned

to guard duty in the railroad yards of Vladivostok--and this incident

needs telling. I was assigned to a post along the railroad tracks

guarding a long warehouse where supplies were being brought in from the

ships. The railroad was right next to the shoreline of Golden Horn Bay,

the source of all of our supplies. (See picture) There was a trainload

of supplies on the track waiting to be unloaded. Due to the extreme

poverty of the civilian population they raided the supply trains

regularly and carried off anything that was loose. I was one of several

guards posted at intervals along the railroad, and at stated intervals

each one of us was required to call in, “All’s well on Post #3" and this

would be picked up and repeated up the chain to the Sergeant of the

Guard. I was farthest away from the Guard House and was instructed that

I was to let no one cross my post; that I was to halt them, first in

English, next in Russian and then in Japanese and notify the Sergeant of

the Guard. The night was cold and the moon was shining brightly and I

felt quite alone out there. I was just a kid and was unfamiliar with my

weapon and frankly, I felt very inadequate to my responsibilities. It

was about two o'clock in the morning and very quiet. Suddenly I heard

the sound of marching feet in the distance approaching me from beyond

the warehouse area. The marching became louder and louder and soon there

came into view a large body of troops, all marching toward me with

bayonets fixed to their rifles glinting in the moonlight. Here they came

marching relentlessly towards me and I was under orders to allow no one

to cross my post. I concluded that one little inexperienced guy like me

had no business tangling with these people. There were two battalions of

them, about 800 officers and men.

I decided that prudence dictated that I not try to

halt them. I didn't want to be a dead hero so self preservation told me

to get out of sight. I spotted a large packing case stacked against the

warehouse and quickly got inside. I watched them march by; they were

Japanese troops, and as soon as they were gone I resumed walking my

post. I waited until reporting time and then called in, in a loud voice,

“All's well on Post #3 I”. I am not proud of my actions, but it seems in

retrospect that I used good judgment. No harm came of the incident and

no one ever questioned me about it.

While in Siberia I had the opportunity to travel as

a Red Cross Guard from Vladivostok to Verkhneudinsk, near Lake Baikal

via the Trans-Siberian Railroad, about 1000 miles inland. Part of the

27th Infantry was stationed there.

Another incident which affected my entire future

happened during the winter of 1919--1920. An arsenal containing arms and

ammunition was located a short distance from our barracks. The arsenal

was in a deep excavation surrounded by steep banks on all sides. It was

a vital installation. I was detailed on guard duty to patrol the

perimeter around the top of the depression containing the arsenal so

that as I patrolled the area I could observe all sides of the arsenal.

As I was walking my post I became aware of the fact that someone was

down in the area of the arsenal. I called out to them and demanded that

they come up. As a response, they began chucking rocks at me. I didn’t

know how many individuals were involved. I heard someone crawling up the

bank and I went to that point with my rifle at the ready. All at once a

head appeared above the bank and I feared that I was under attack. On

the spur of the moment I swung my rifle in the direction of the person

emerging. He was below me and fortunately my rifle connected with the

object; apparently I had hit him on the head. He gave a cry and rolled

down the bank. The blow with the rifle caused the rifle stock to break

in two. I called the Sergeant of the Guard and reported the problem. We

searched the area with flashlights and no trace of the person was found.

We decided that whoever it was had left the area. My rifle was replaced

and I continued my guard tour and was relieved at the proper time.

The next morning after daylight the sentry then on

duty discovered the body of a Chinaman near the arsenal. He had either

died of his injuries or had frozen to death. A full investigation of the

affair was made. I was worried about the possible results when I was

being questioned. I thought, of course, that I was somehow in a great

deal of trouble because of the action I had taken. There were several

Russian officials from Vladivostok at the hearing. Instead of being

censured I was, to my surprise, commended for my action. I was rewarded

by a promotion from Private to Private lst Class and was given an

assignment to duty at Regimental Headquarters in the offices of Colonel

Fred w. Bugbee. This was really the beginning of my career in military

administration.

Christmas in Siberia in 1919 was pretty much a

non-Christmas. Rations were scarce--it was bitter cold and we were a

long way from home. The YMCA distributed to each of us a can of

chocolates and we each received an orange. I just learned through

reading General Graves book that some lady in California kindly arranged

for a shipment of oranges so that each serviceman could have one for

Christmas. Bless her! The YMCA served us a Christmas breakfast of hot

cakes, a most unusual treat. Few goodies were available but occasionally

I was fortunate enough to get a detail as guard at Red Cross

Headquarters in Vladivostok where the nurses would come up with some

English marmalade and tea and toast. I surely relished it. (See

pictures) Some of the fellows would sometimes get into a happy mood from

bootleg vodka made from potato peelings.

There was not a great deal of snow around

Vladivostok; however, it was terribly cold and windy. Often the

temperature was from 30 to 50 degrees below zero.

There was much more snow further inland. We were

furnished huge sheepskin coats and beaver hats, gloves, knee length

German wool socks, light snow packs made of soft doeskin and worn over

the socks but inside the heavy shoes. Being young I managed pretty well

to keep reasonably comfortable.

In the early spring of 1920 word came down to us

that we were withdrawing from Siberia and going back to the States. This

however, proved to be untrue.

We boarded the US Army Transport Crook. Golden Horn

Bay was frozen over and we had to have an ice breaker clear a channel

ahead of us to get us out into the Pacific. Those in charge, of course,

knew our destination, but we, the troops, thought for sure that we were

enroute home. After we had gotten under way it was made known to us that

instead of going to the States we were going to the Philippine Islands

for station. We were a sad lot of fellows. Our ship took us to Ching Wan

Tao, China, a short way from Peking where we stopped a short time. It

was here I picked up the brass plate, bookends and God of Happiness

which I prize highly. We then went to Nagasaki, Japan and then on to

Manila. The weather got warmer and warmer and we were unprepared for the

abrupt change in climate. We had only wool clothing to wear enroute.

Finally we arrived in Manila, P. I. and were placed in a tent camp near

the harbor where we were kept in quarantine for about six weeks. Finally

we were transferred to the Cuartel de Espania in the walled city for

permanent station.

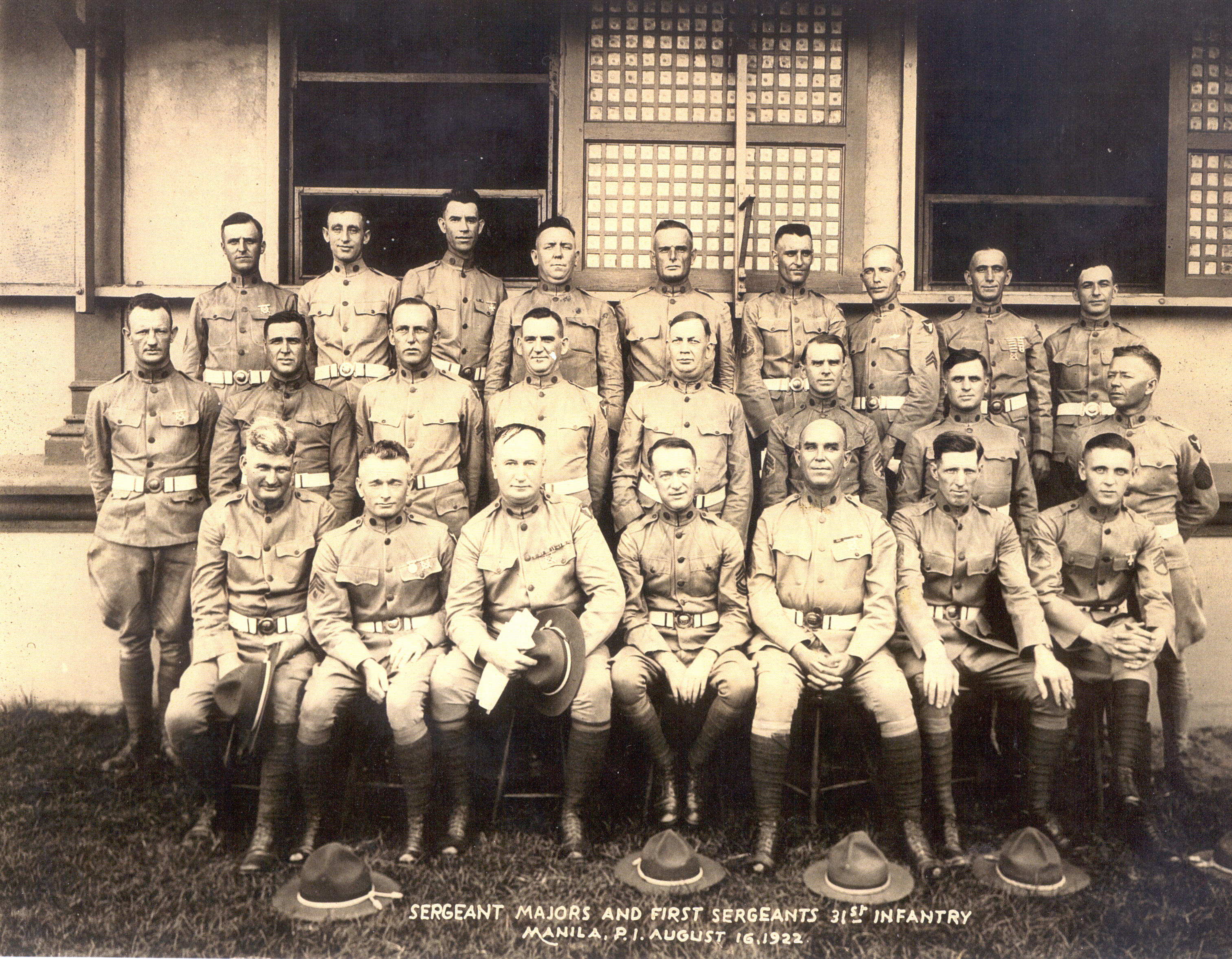

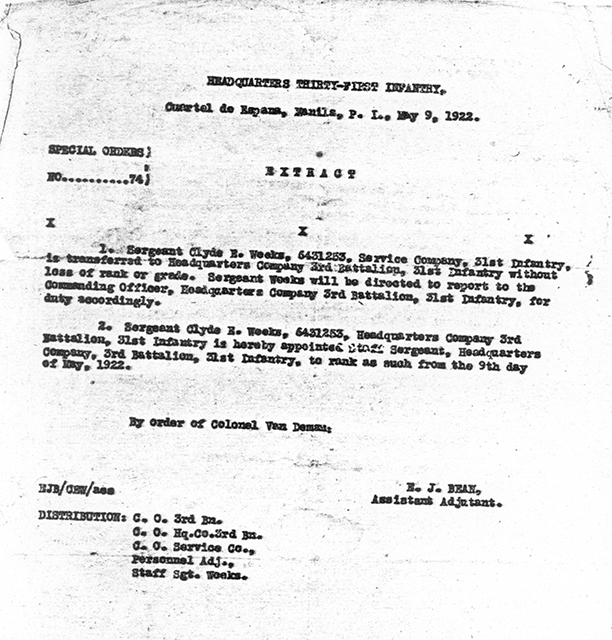

I learned the world of military administration

rapidly. I studied diligently and was given opportunity to become

proficient in Army paperwork. I enjoyed what I was doing and was

promoted rapidly. I jumped the rank of Corporal and was promoted to

Sergeant and then to Staff Sergeant. At the end of my first three years

enlistment at the age of 19, I had become Battalion Sergeant Major of

the Third Battalion of the 31st Infantry. In those days that was an

accomplishment because promotion was very slow and I was very young. I

took a lot of time to practice improving my handwriting and I taught

myself how to type rather rapidly with the hunt and peck system. This

proved to be most helpful as I continued my military career.

31st Infantry in Manilla in March 1922

May 5, 1922

First Tour of Duty in the Philippine Islands

During my first tour of duty in the Philippine

Islands after leaving Siberia I had three close friends with whom I

clubbed around. We went to U.S.O. dances and were just good friends

running around exploring Manila and all of its environs. One of the

fellows was a very accomplished pianist so we often gathered at the USO.

He played the piano and we sang and danced. He had spent considerable

time in Hollywood before coming to the Philippines and was quite worldly

wise. We didn’t drink except for an occasional beer but on one

particular night he suggested that we visit Chinatown. While there he

entered one of the shops and bought a small matchbox. I had no knowledge

of the contents of this little box. He got us all together in an out of

the way place and suggested that we try a new experiment. He said that

he could transport us to a new “high”. He had a penpoint, the back of

which he used as a little scoop.

He led off by filling it with white powder

which he then snuffed up each nostril. He then enticed each one of

us to do the same and share the experience. I really didn’t know

what it was all about but was game to going along with the others.

We followed his example and “took a snort” of what must have been

cocaine.

The effects were almost immediate. We decided

to do a lot of walking through the area and were really feeling

exhilarated. I am sure that we walked literally miles before the

effects of the drug wore off. It was such a false stimulation.

Finally we all returned to our barracks pretty much exhausted and

went to sleep. The next morning when I awakened I realized that I

had been tampering with drugs of some sort. I felt completely

drained of all energy and I became frightened over the possibility

that I might become addicted. I knew then that this buddy whom we

all admired so much for his talent was likely a dope addict. And I

made up my mind right then and there that I didn’t want to get

involved and resolved that never again would I fool around with or

be enticed by anybody that played around with drugs. I was doing

well in the Army and using dope was an offence for which anyone

could be dishonorably discharged from the service. I really was

shocked into a realization that I had risked my entire future in

this one instance.

The four of us continued to club around

together but we were never again tempted. The man who tried to

introduce us to the habit was eventually dishonorably discharged

from the service and sent home.

I am grateful for the lesson that this taught

me because later on I had many opportunities to council young people

in my church assignments and prevent them from making a similar

mistake or help them with a problem they had already acquired. The

lesson to be learned here is to never have a first experience.

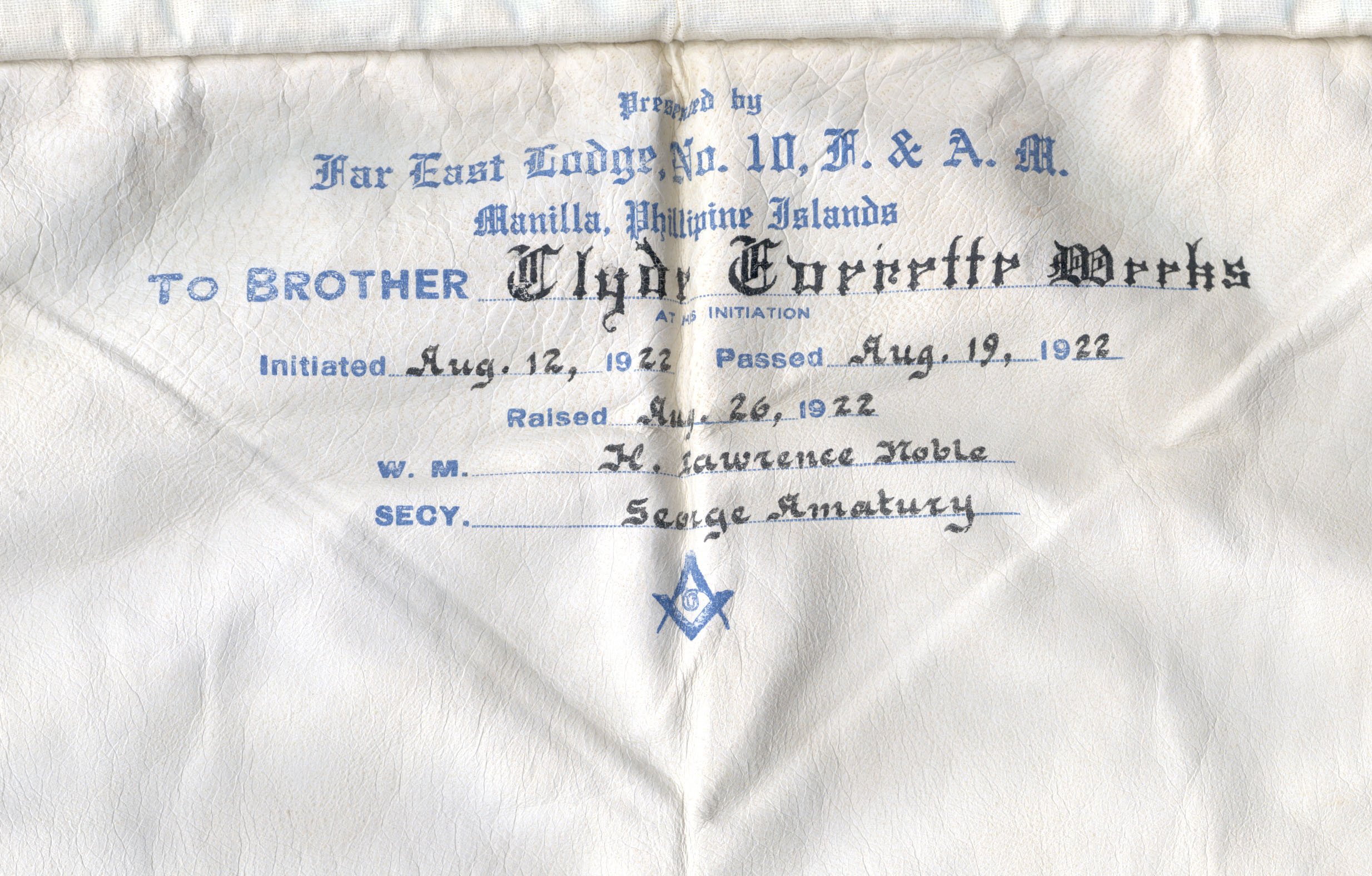

THE

MASONIC ORDER IN MY LIFE

During my boyhood my Uncle Ralph, my father's

brother, stood out as an example to me as an ideal man and one whom

I would like to emulate.

He was a fine looking man physically; over six

feet tall and I thought him to be very handsome. He was a success in

business as a chiropractor and later was General Agent on the Pierre

Marquette Railroad System. He was always well dressed and I aspired

to become like him.

Uncle Ralph (Aunt Angie's husband) was

affiliated with the Masonic Order and belonged to the Knight

Templars. When they had parades the Knight Templars were always

mounted on black horses with plumaged headgear. The Knights wore a

saber as part of their dress. I made up my mind when yet a kid that

when I grew old enough that I too would become a Mason.

Upon arrival in Manila from Siberia I had

little to do to take up my spare time and learned that there was a

Masonic Lodge organized there. Upon making inquiries I was soon

invited to join Far East Lodge #10 of the Free and Accepted Masons.

I was actually not old enough, 21 was the age at which one could

become a Mason, but my military record had not yet been changed to

my real birth date, and it enough, 21 was the age at which one could

become a Mason, but my military record had not yet been changed to

my real birth date, and it indicated that I was.

The opportunity of becoming a Mason thrilled me

and I devoted most of my spare time in learning the rituals and

procedures. I was soon appointed secretary of the Lodge and learned

all of the administrative work. I became really engrossed in lodge

work and set about memorizing all the secret rituals. Our lodge met

at least once a week and I was given many opportunities to assist in

putting on the work in all of the different positions. Most of the

lodges in Manila were Spanish speaking and they had difficulty in

putting rituals on in English; so several of us formed a degree team

which took us from lodge to lodge conferring degrees on new

initiates. Because of my quickness of mind and ability with the

ritual, I was very soon appointed junior and then senior deacon in

our lodge. Before returning to the States, I was elected Junior

Warden.

After returning to the States in 1927 and again

being assigned to Fort Douglas, I affiliated again with the Masonic

Order in Salt Lake City and attended lodge regularly. I had however,

married a Mormon girl and had been attending Sunday School and

Sacrament Meeting with her. I’d been aware of the fact that in Utah

the Masonic Order would not permit active Mormons to belong to the

Masons. Some of my Masonic brethren learned that I had been

attending L.D.S. services and reported it to the local Masonic

authorities. Upon arriving at lodge one evening I was stopped from

entering and told that the Master of the lodge wanted to see me. He

took me into a room and inquired if I’d indeed been going to L.D.S.

services and I told him that I had, whereupon he told me that

because of this some of the brethren objected to my attending the

lodge any more. I have never returned to a Masonic Lodge again even

though I have held an honorary lifetime membership conferred upon me

by Minerva Lodge #41 in the Philippine Islands.

I am grateful for the experience I had in the

Masonic Order because it kept me doing worthwhile things and in a

way, took the place of church activities for me. The lodge has high

moral requirements and I feel this experience prepared me in a large

degree for my later assignments in the Church. Much of the

administrative details were similar in the lodge and the church.

Military Orders

Masonic Lodge White Leather Apron From the Philippine Islands in 1922

MARRIED LIFE AND SERVICE CAREER

I really enjoyed my assignment at the Fort and

quickly found favor with the personnel there and made many friends

quickly. Several of us used to go to dances in the town for

entertainment. There always seemed to be plenty of pretty girls

available to date. The most popular place at that time was the

Bluebird where many young people liked to gather. One evening I went

there with some friends and happened place at that time was the

Bluebird where many young people liked to gather. One evening I went

there with some friends and happened to get acquainted with a group

of student nurses from the L.D.S. hospital. It was at this time that

I met Bert ( Bertha Margurite Larsen) and some of her friends. We

hit it off almost immediately. After this I spent many, many

evenings at the L.D.S. Nursing Home and had a lot of fun with the

nursing group of students. They really took me into their friendship

circle and many evenings were spent in the diet kitchen making candy

and goodies. The superintendent of nurses was especially kind to me

and permitted Bert and me to have opportunity to be together a lot.

We were really attracted to each other and were almost immediately

going steady. There was one barrier which was difficult to overcome

and this was that Bert was a very fine L.D.S. girl and I was a

non-Mormon. Bert had been orphaned when she was 12 and the small

inheritance which she received financed her training at the

hospital.

The fact that I was not a member made it very

difficult for her because she was truly in love with me. During the

year of our courtship this fact was always troublesome to her. She

did get to go to church while in training and I accompanied her on

many occasions. We attended at the L.D.S. Hospital Chapel at this

time. Bert had four roommates who were very close to her, all

attractive girls. When Bert decided she could not go with me, a

non-member anymore, I would play one of these girls against the

other and would usually show up with one of Bert's roommates as my

date. Whenever she was reluctant to date me there appeared a dozen

red roses at her door. I gradually broke down her good intentions

and would get my date. I put some unusual pressure on her because I

thought so much of her and when I sensed that I was losing ground, I

took unusual measures. She invited me to a formal party at one time

and I didn't have a formal outfit to wear so I devised a scheme

which I thought might solve the problem. I fibbed a little and told

her that I had been ordered to take a group of prisoners to Alcatraz

in California. This, of course, was not true, however: a friend of

mine did go on this assignment. Before he left I wrote several

letters to Bert and had him mail them from San Francisco. When I

"returned" I was warmly received and things started going again. We

talked of marriage because we were both in love but she was adamant

about not marrying out of the church. I was just as sure that I

could persuade her otherwise.

There was a place in Farmington, a sort of

Gretna Green, where people could go to get married without any

formality. A train from Salt Lake City used to run out there on

schedule. On November 7, 1924 I persuaded Bert that we should go to

Farmington and get married.

It was a cold and snowy night when we boarded

the train and upon arrival at Farmington in the foul weather, we

learned that the judge had gone out of town; so we had no choice but

to re-board the train and return to Salt Lake City, disappointed, of

course, as we were so very much in love. I took Bert back to the

hospital and I returned to Fort Douglas.

The following morning I went to the office as

usual. I still had marriage on my mind. About 9 a.m. I called Bert

at the hospital and asked her if she still wanted to get married.

She said, "Yes, if it can be worked out." I said, "you meet me down

at the County Clerk's office in an hour."

We met as scheduled and went into the County

Clerk's Office and applied for a marriage license on Nov. 8, 1924,

my mother's birthday. A Mormon Bishop by the name of Graham was the

County Clerk. He discerned that we had no families and had made no

arrangements for marriage so told us that he was a Bishop and could

perform the ceremony right then and there. He called in two

secretaries as witnesses and we were united in marriage.

Girls in nurses training were not supposed to

get married so we decided to keep it a secret until after her

graduation in June; but when the vital statistics came out in the

newspaper the following Monday, our marriage was listed and picked

up by the girls at the nursing school.

Her breach of the rules was forgiven and she

was permitted to finish training and was graduated in June 1925 as a

full registered nurse.

After our marriage we set up housekeeping in a

darling apartment at 606 6th Avenue in Salt Lake City since all knew

of our marriage and there was no need for secrecy. Bert continued

with her training and I with my assignment at Fort Douglas. We were

very happy during these months.

After her graduation I thought it would be nice

to take Bert on a special honeymoon and re-applied for assignment to

the Philippine Islands. So, after a happy summer in Salt Lake City,

I at the Fort and Bert working as a nurse for Dr. Feno Shafer (whom

I later learned was my future brother-in-law's uncle), we left for

the Philippines on Sept. 25, 1925. In the interim we were very happy

to learn that Bert was to have a baby.

On

arrival in the Philippine Islands we had very nice accommodations

furnished us on top of the wall of the old walled city of

Cuartel-deEspania in Manila where Clyde Jr. was born in the

Sternberg General Hospital in Manila on Nov. 18, 1925.

As stated, our house was on top of the wall and

in the courtyard below was an area in which the children used to

play. We thought they were safe in every way here and had no concern

over them until one evening a child came screaming from the play

area exclaiming that a big snake was there. I joined with several

other fathers using clubs and metal bars etc. and we together

dispatched the 20 foot long python which had come out of one of the

recesses of the wall. It was not unusual for a python of this size

to eat a small pig alive, so the children were in real jeopardy.

Clyde Jr. was in the play area along with the others and was close

to and exposed to the snake, so we felt most grateful to have

rescued the children before any mishap occurred.

During this time I was very active in the

Masonic Order and spent a great deal of time in their activities.

Bert applied to join the Eastern Star, the women's organization of

the Masons, but I was told that she would be rejected because she

was a Mormon and it would be wise if we would withdraw her

application to avoid embarrassment. This we did, but I continued in

my activity.

We were rotated back to the States in the Fall

of 1927. I asked the War Department to return me to Fort Douglas and

they did so. We were happy to return to Salt Lake City where we were

among our friends. We took up residence on Brazier Court which was

just one block from the Fourth Ward chapel where Bert became

affiliated and where I attended with her. The Saints were very

friendly in this Ward and really fellowshipped us, particularly the

Bishop, William F. Perschon, whom I learned to love as a father.

On December 24, 1927, I was baptized in the

font in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, much to the joy of my dear wife

and her family. I was confirmed a member of the church on January 1,

1928 and have been active ever since in practically every capacity

available to a Priesthood holder.

On October 7, 1929 we were sealed in the Salt

Lake Temple and Clyde, Jr. was sealed to us. Yvonne Sharee was born

on September 4, 1930 and Michael Wayne on August 28, 1938, these two

being born under the covenant.

January 7, 1925

Second Tour of Duty in the Philippine

Islands

I returned to the United States in 1923 and was assigned to Fort Douglas. While there I attended lodge in Salt Lake City. In 1925 I again went to Manila and resumed activities with the lodge where I first joined the Masonic Order. In 1926 I was elected Senior Warden and in went to Manila and resumed activities with the lodge where I first joined the Masonic Order. In 1926 I was elected Senior Warden and in 1927 was elected Worshipful Master and became a member of the Grand Lodge of the Philippine Islands. I served in this position for one year; upon the conclusion of which the lodge honored me by awarding me with a beautiful Past Master's Apron and a Past Master's Jewel which consisted of a large gold square and compass set with a lovely diamond. This diamond now is in Helen's engagement ring.

Clyde in 1925

Transmittal of Commission to Second Lieutenant

Clyde E Weeks, Sr.

January 1, 1926

Clyde Jr as a baby with Clyde Sr

February 6, 1926

Clyde in Manila

1926-04-06_Bertha & ClydeSr & Friend visiting in Manila

May 5, 1926

Note from Clyde to Bertha & Clyde Jr.

Fort Douglas

When I came to the States from the Philippine

Islands in 1923 I was supposed to have been given my assignment from

the military, but my assignment had not come through so I stayed at

Fort McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay for 2 or 3 weeks

before my orders finally came from the War Department. They were

sending me to Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City.

I was a Battalion Sergeant Major at this time

and they had to find a spot for that rank before assigning me.

Perhaps this assignment was the hand of the Lord in my life.

When I got on the train a very tall man, the

conductor on the Pullman approached me and inquired about my

suitcase which was hand made in China.

He asked me if it was my case and I told him it

was. He then informed me that he had an identical case in the next

compartment. I was in uniform and rather inconspicuous as many

uniformed men were traveling during this time. He asked me if I had

ever been in Salt Lake City before. I told him that I had not

whereupon he said, "I could make it a lot easier for you to get to

Fort Douglas." He told me he could have a taxicab and driver waiting

for me to take me wherever I wanted to go and besides, he could make

it worth my while too for a little favor. Inasmuch as my suitcase

was just like his, all I would have to do was to take his suitcase

off the train instead of my own. He said I would be met by the

taxicab driver who would take me to an address on Regent Street

where my suitcase would have been delivered previously and we would

exchange suitcases after which the driver would take me on to Fort

Douglas. For this service to him he would give me $20.00. I took him

up on the proposition since I was young and alone and didn't really

know where I was going in Salt Lake City, so when the train arrived

I carried his suitcase off the train and was met by cab and driver

and taken to Regent Street where I went upstairs in a building and

we exchanged suitcases. I was given $20.00 and taken on to the Fort

Douglas.

I learned later that Regent Street was the “red

light" district of Salt Lake City. It was only later too, that I

realized that I was no doubt involved in some kind of smuggling deal

as it was during the days of prohibition. Had I been caught I could

have been in a great deal of trouble. It could have jeopardized my

entire military career and my whole life could have been changed.

This was in 1923 when I first came to Fort Douglas.

Shortly after I joined the church we were

assigned quarters at Fort Douglas, a brand new home located right in

the mouth of Red Butte Canyon. Sharee was born in the Holy Cross

Hospital after we moved to the Fort. I was permitted to witness her

birth as our doctor was a dear friend, Dr. Morgan Coombs. Clyde Jr.

and Sharee spent their happiest childhood days at Fort Douglas. The

entire Fort became their playground and they had many friends there.

Red Butte Creek ran to the rear of our home and Clyde Jr. spent most

of his spare time along the creek and in the canyon. He often would

bring home rattle snakes which he would capture and skin and make

belts and hat bands out of them.

These were the years of the great depression

which began about 1928 with the closing of the banks in January

1930. We were fortunate in not being affected by it. Working for the

government provided steady paychecks and we had a good home while

many people in the city were literally starving. We were able to buy

bread, freshly baked at 2¢ a loaf and had commissary privileges. Our

dollars were worth more on the market place in town too, because

many merchants had sales selling at cost rather than go broke.

We continued to go to church at the old Fourth

Ward using streetcar transportation. We made the journey several

times a week to keep up with all of the meetings. Fort Douglas times

were happy times in our life.

Clyde & Bertha Swimming in the Great

Salt Lake

Certificates of Baptism & Ordination

Ordination to the Office of Elder

Sealing Certificate for Clyde & Bertha

Clyde Sr's Scoutmaster Bandalo 4th Ward Salt Lake

Clyde Sr, Bill Burton & LaMont Preece - Sunday School Superintendency

January 1, 1932

Clyde E Weeks in 1932

January 1, 1933

Clyde, Bertha & Sharee in 1933

Clyde Military Photo

Clyde Sr at Fort Douglas

January 1, 1938

Clyde E Weeks

May 8, 1938

Mother's Day Card from Clyde Sr. to Bertha

August 28, 1938

Bertha Holding Michael

In late 1937 Bert was pregnant with Michael and the

doctor found a small lump in her breast which he thought was an enlarged

milk duct. He advised nothing be done until after the baby was born.

Michael came on August 28, 1938, also at Holy Cross Hospital with Dr.

Morgan Coombs as obstetrician. Shortly after his birth I was ordered to

summer camp at Fort Lewis, Washington. While we were gone, all army

wives desiring it were given a free physical examination. Bert

participated in this and I was shocked when a telegram came to me at

Fort Lewis informing me that Bert had cancer of the breast and advised

me to return immediately. I drove from Fort Lewis only stopping for gas

and on my arrival home, the surgeons performed a radical mastectomy on

her left breast. Bert healed quickly and it was thought that the cancer

was entirely eliminated and we were told the operation was so successful

that if she could go for two years without any reoccurrence she would be

safe.

Shortly after Bert's operation the Regimental Staff

of the 38th Infantry of which I was a member was sent to San Antonio,

Texas to prepare for the transfer of the entire regiment to San Antonio.

I came back to Utah and got my family in August of 1939.

In San Antonio we established a home on Pershing

Drive and were soon very busy in the Ward there. I held several

positions of leadership and was involved in the fund raising effort to

build one of the first chapels in that city. Prior to this all they had

was a Mexican Branch. We were really enjoying our stay in San Antonio

and Bert seemed to be perfectly well.

After several months we were transferred to

Brownwood, Texas where I was an Adjutant General in the 8th Army Corps.

Almost 2 years had elapsed since Bert's operation. In Brownwood we

rented a nice home and were very happy there. I was very busy with

pre-war preparations as Hitler had already invaded Poland and it looked

as though war were imminent.

One day Bert and I were playing miniature golf.

When she stooped over to pick up a ball her hip caught and she was

unable to stand up. The next day I took her to the osteopath and he said

she had a little arthritis and prescribed some treatment which was

ineffective. I decided that it would be wise to take her to the Military

General Hospital. Bert kept the appointment alone. About 2 o'clock in

the afternoon she called me at my desk and told me that the Colonel

would not give her the results of the X-Rays until I could be present.

Bert, being a registered nurse, suspected the worst. I went immediately

to the hospital and they showed me the X-Rays which confirmed Bert,

being a registered nurse, suspected the worst. I went immediately to the

hospital and they showed me the X-Rays which confirmed that cancer had

invaded her pelvic region. The doctor told me that she would likely die

within 3 months.

We transferred her to the Army General Hospital at

Hot Springs, Arkansas for treatment. After several weeks in which I made

numerous plane flights to see her, they told me that there was no cure

for her condition and advised me to take her back to her home in Utah.

I drove her and the children to Provo in my car and

established them in a comfortable apartment on First East and First

South. I arranged for Dorothy Tuttle, one of Bert's old roommates while

attending nursing school to look after her. Edna and Wilford Larsen took

Sharee and Michael and Clyde, Jr. went to stay with Seth Larsen so that

he could continue his high school studies at Provo High.

I had to immediately return to my duties in

Brownwood. It was only a few days later that I received a telegram that

Bert was worse and had been taken to the hospital in Provo. I drove back

again and was with her in the hospital for the last few days of her

life.

When all seemed hopeless and we knew she was

enduring terrific pain, her brothers Grant, Seth Wilford and I gave her

a special blessing and asked our Heavenly Father to take her home which

he in His mercy did in a matter of hours on October 19, 1941.

During all of this time I was in the military under

special orders so had to meet military deadlines all of the time. Clyde,

Jr. stayed on with Seth and Lilly until he graduated from High School in

May 1942 after which he joined the Marine Corps on February 15, 1943.

October 10, 1938

MY MILITARY CAREER

I received my commission in the service initially

on February 10, 1925 at age 22 before I was married. For a time I was

working in a duel capacity, as an enlisted man as Sergeant Major 31st

Infantry and as a reserve officer, Second Lieutenant in the

Quartermaster's Corp. In order to qualify for this, I took many

correspondence courses as well as class work which was available to

servicemen. From the

Quartermaster's Corp I transferred to the Adjutant

General's Department and was made a First Lt. Reserve in that

department. Just before Bert died and before World War II I was made

Captain with a permanent commission. Needless to say, she was very proud

of this achievement.

After her death, just as soon as it was learned by

the military, I received several offers to important positions in

Washington, one of which was Chief Signal Officer, Washington D.C.

extending me an opportunity to be transferred to that office which was

engaged in organizing the executive control division. I also had a

letter from the Adjutant General of Headquarters Third Army suggesting I

not go to the Signal Office in Washington because he had other plans for

me. He came personally to Brownwood to talk to me and suggested I needed

a change of scenery but said, "Would it not be better to make a change

to a location where you would have more opportunity to increase your

professional advancement." Soon after this a letter came from Washington

to the Third Army asking them to select three outstanding officers with

the rank of Captain or higher to attend Command and General Staff School

at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. These officers had to be "especially well

qualified, possess the required military experience and education to

properly pursue the course, and to have demonstrated especial fitness

for command and staff duty." I was selected, I don't know why with my

educational background, and was ordered to duty as a student at Fort

Leavenworth.

The only way I could have qualified was that I was

an outstanding officer and was on duty at Third Army Headquarters as an

Adjutant General. All of the other men selected (a class of 342 men from

allover the country) were highly educated, most of them were graduates

from either the Army or Navy Academy. This was my competition. Poor me

with a 7th grade formal education. However, I made it the hard way

working about 24 hours around the clock. My advantage was that I had a

lot of skills in military administration through my experience. My

greatest handicap was math, but I made some good friends who helped me

get over that hurdle. My competition did ballistics with slide rules,

while I had to work the problems in long hand arithmetic.

I graduated with an excellent rating and returned

to San Antonio at the completion of this strenuous three months course

which lasted to the end of March 1942--the first such course taught

after Pearl Harbor. Upon arriving back in San Antonio and the Third Army

for assignment, I was transferred from the Adjutant General Staff

Department to the General Staff Corp and was sent as a member of the

General Staff to England. The Adjutant General Staff is purely

administrative, but the General Staff is like a board of governors of a

corporation. Here is where all the business is transacted for a regiment

and all the information is gathered for the General to make his

decisions.

Almost the next day after arriving in San Antonio I

was called to the General's office and told that I had been selected to

go to London to become a part of General Eisenhower’s staff. The General

asked me how soon I could be ready to go and I told him, "At once." The

next day I was on my way to Washington, D.C. I sold all of my household

goods and all I possessed right on the spot in Texas before leaving. The

purchaser was a pharmacist in the service, a First Lieutenant to whom I

had previously rented our house upon Bert's death.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

I reported to the War Department in Washington D.C.

and was briefed and given my orders and designated as an ambassadorial

currier with a pouch chained and padlocked to my left wrist. This

contained secret war communications which I was to deliver to General

Eisenhower. The key to the pouch was in London from Washington D.C. I

was billeted in a hotel in Baltimore for a couple of days to await

instructions which arrived late in the evening. I was picked up and

whisked down to the wharf of the bay, put aboard an English amphibious

clipper plane called the S. S. Burwick. The plane had been pretty well

stripped and we who were aboard sat on the floor. Very few planes were

flying across the Atlantic at this time. I have a memory of circling

Washington and Baltimore in the middle of the night and then taking off

for Newfoundland where we landed on the water and refueled. After

leaving Newfoundland we were in hostile territory subject to German

surveillance. We seemed to fly from cloud bank to cloud bank until we

landed in the bay at South Hampton,

England, again on the water. I have a short snorter

one dollar bill we all signed on this trip. (This bill was given to

Michael)

I was assigned to a hotel in Grosvernor Square. At

that time nightly bombing raids from Germany were in progress. My

attitude was that I did not care whether I got hit or not, so I took

none of the precautions of going to bomb shelters, etc. I was heart

broken and wandered about the streets of London on my free time as

though there were no war on. My children were in the States, not without

problems as to their care, and here I was with a new assignment in a

strange city with no friends or acquaintances, working long, grueling

hours, day in and day out. Theaters were closed; no lights were allowed

after dusk; it was a very dreary, dismal, most unhappy time of my life.

Bertha Marguerite Larsen - Clyde's First

Wife

Military Promotion

February 2, 1942

Clyde Sr, Michael, Sharee & Clyde Jr

February 2, 1942

Graduate Diploma for The Command and General Staff

School

A FAITH PROMOTING INCIDENT

During

World War II, I was an officer in the U.S. Army and was stationed in

London. On one occasion I was ordered to make a trip from London to

New York under military orders. At this time the passage was

hazardous because of enemy submarines. Most ships were sent in

convoy with large cruisers and destroyers as escorts. We made a

convoy of three passenger ships and had some escort. Before

embarking at Belfast, Ireland, word was received from Intelligence

that our convoy might be attacked. All women and children aboard

were removed and our ship, a large ocean going liner which had been

converted to transport use, was permitted to sail in the convoy.

About 900 miles out from New York we ran into trouble. The naval

escort was forced to leave us to respond to enemy action elsewhere,

and we were left alone to continue toward New York. That evening

dinner was served at about 7:00 p.m. as usual and I went to the

dining salon. We were supposed to wear our life jackets at all

times. This particular evening I was busy on some administrative

work in my cabin and when the gong sounded I went in to dinner

without my life jacket. While at dinner alarm was sounded. Our ship

had been sabotaged and set afire from stem to stern in the matter of

moments. The night was dark and we were in heavy seas. I tried to go

back to my stateroom but was blocked by flames. The entire ship was

a holocaust. The life boats were soon aflame too, and all passengers

above deck were huddled in the forcastle. Soon it became apparent

that we had the choice of abandoning ship or burning to death. We

remained aboard as long as possible but soon the decks beneath our

feet were hot and burning fast underneath. Loading nets were put

over the side and we all scrambled down into the water. A few life

boats were saved and a few hatch covers. The night grew steadily

darker and the seas higher. I was then in the water with no life

jacket and I could not swim. I caught hold of a hatch cover and hung

on.

At this point I felt that I would likely perish. All of the time I was praying to my Heavenly Father that I might be saved and I promised Him that if He would do this I would seek to do His will the rest of my life. We were in the water for hours and hope was fading.

Then we saw the lights of a ship. We did not

know whether it was enemy or our own. It proved to be a U.S.

Destroyer, the USS Brooklyn. We were soon safely aboard and on our

way to New York. I know that my Heavenly Father answered my prayer

and that I have a mission yet to fulfill here on earth and I will

forever try to do what He wants me to do.

Statement of Military Service

July 7, 1944

Clyde Sr, Sarah Maude & George Clarence Weeks

US Army Command & General Staff School in Fort Leavenworth

Kansas-Group G1_December 1944-February 1

May 5, 1947

Clyde & His Cousin "Babs"

November 4, 1947

Citizens Food Committee Letter to Clyde Sr

January 1, 1948

THE HOW, WHEN AND WHERE OF A BEAUTIFUL COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

When I returned from the Service I went to stay

temporarily with Clyde Jr. and Helen. I soon made a special visit to

the church offices to see Elder Harold B. Lee who was then a member

of the Twelve. He was my Stake President when I joined the Church

and we had become very good friends, I having visited in his home on

a number of occasions. He had shown a special interest in me through

the years. I went to talk to him about my future. He knew that I was

hard hit by the death of my first wife whom he knew very well. In

our conversation I made it clear to him that I had no intention of

ever marrying again because I did not want to take the chance of

repeating the sad experience such as I had previously undergone. He

was very generous of his time and we visited quite a while. As I was

about to leave he said, "Clyde, I am impressed that I should give

you a special blessing." He gave me a beautiful blessing but

included in it the admonition that I should marry again and would do

so. He told me that there was a special mate out there waiting and

that when I met her I would know her and that I would marry her and

have a beautiful future with her. I doubted this part of the

blessing because I had no intention of ever marrying again.

I went

to Provo and found a house that had just been completed and

negotiated for its purchase. Clyde Jr. and Helen lived in a rented

apartment in Orem so I invited them to move into the new home with

me with an arrangement that I would more or less board and room with

them.

I lived there but a short time when I was

called into the superintendency of the Sunday School in the

University Ward. Upon searching for employment, I located a position

as Assistant Manager of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. I had no

special qualifications in this field, however, I learned the work

rapidly and it turned out to be a pretty good job. I stayed with

them for 10

½

years.

During the first little while in Provo I had a

few dates and socialized a bit, however, nothing serious developed.

There was one association which might have developed to be more

serious. About this time Sharee decided to get married although I

guaranteed her funds to attend BYU if she so desired. She elected to

get married though and so I arranged a very beautiful reception for

her and Keith in the recreation hall of one of the Wards on 8

November, 1948. It was a fancy affair including an orchestra for dancing. This

lady friend stood in as my partner in the reception line and many

assumed that I would likely marry Marian Brandly. However, things

began to happen rather rapidly in my life after that.

I met an old friend, Pat Kauffman, who was

attending BYU and who used to teach Sunday School for me when I was

Superintendent in the 4th

On the Firday following Thanksgiving in 1948 I

was working in the Singer Shop when a very attractive young woman

entered the store. I was in the rear of the store but I saw her and

was impressed thinking she was a darn cute gal. I seemed that she

had a problem with a hemstitching device and needed same help in

making it operate. The floor girl waiting on her called me for help

and that is when I met Emily. Emily had heard of me through our

mutual friend and all at once it dawned on us that we were the

people that Pat had been trying to arrange a blind date for. We

chatted a bit and got acquainted and I then and there knew that I

must get better acquainted with this girl. I proposed that we go out

that evening to a show and was a bit surprised that she accepted. We

set the time and I told her to be ready because I would be coming in

a taxi as I. had not yet acquired a car. I remember that it was

snowing lightly that evening. We went to the Paramount in the taxi.

I was so impressed and so thrilled with the experience that I didn't

see much of the show; I spent the time admiring my date.

We walked home in the snow and Emily invited me

in. We lit the fire which had been laid. This added a great deal of

romance to the affair.

We seemed to be mutually smitten with each

other; it seemed like a case of love at first sight. The next day

being Saturday, I borrowed Clyde Jr.'s car and Emily and I went out

to Park Roshee dancing and had a wonderful evening. Before going out

I had a chance to meet the children and fell immediately in love

with all of them. I planned not to have a date on Sunday because I

had a commitment to have dinner with Sharee and Keith in their new

apartment in Orem, the first time I would have seen her new home

after her recent wedding; but the urge became too strong and about

two o'clock in the afternoon I walked over to see Emily and my new

family. We all went to Sacrament Meeting together.

Emily was a member of the choir but sat with

the family and me during the opening exercises after which the

Bishop asked all the choir members to take their places in the choir

to help sing the special number prepared by them for the service.

Emily left me with the children but returned immediately after the

singing of the anthem. The Ward members were agog with speculation.

I had made arrangements to meet Clyde Jr. to

take me out to Sharee's to keep my dinner appointment after which I

returned to Emily's and called a taxi about 3 a.m. to take me home.

On Monday I went directly to Emily's after work and had supper with

the family. After the children were put to bed, Emily and I visited

until the wee hours of the morning before another great fire. The

setting was ideal and I was impressed to ask her to marry me. She

pointed out all the heavy responsibilities that would go with such a

marriage, however, after a great deal of discussion and no doubt,

inspiration she accepted my proposal. Emily's mother and father were

living in her downstairs apartment and we went down to break the

news to them. They were in bed, of course, and mother was

embarrassed because she had her teeth out and her night cap on. She

thought we had gone berserk making so important a decision in so

short a time--four days. However, mother and dad knew that we had

made a firm decision and gave us their blessing. The very next day

Emily made appointments with her Bishop, my Bishop and with Hugh B.

Brown who later became a member of the Twelve. I was thoroughly

interrogated concerning church activities, tithing and my ability to

take care of the family. Each in turn gave their approval, perhaps

some with tongue in cheek.

We did not delay our marriage because about 3

weeks later we were married for time and eternity by Elder Harold B.

Lee on 22 December 1948 (Karen's birthday). As we left the Sal t

Lake Temple all the Christmas bells in the city were ringing and

there was a slight snowfall. It was a very special occasion; it

seemed as though it was done especially for us.

Grandma took me aside one day and told me she

didn’t think we should have any children. Of course, this advice

went on deaf ears. One of the greatest joys of our life in the

person of Jerri Susan came as the result of my ignoring my

mother-in-law's advice; Jerri being Emily and my child which

cemented our marriage and our family. She was born on January 2,

1950, just a year and 11 days after our marriage.

Clyde Sr & Clyde Jr in 1948

June 6, 1948

County Commissioner Filing Article

Melody, Clyde Jr, Sharee, Michael & Clyde Sr

Sacrament Meeting Talk Given July 18, 1948

Clyde Jr., Melody, Clyde Sr. & George Clarence Weeks

Clyde Sr., Michael, Sarah Maude, Clyde Jr., Melody & George

Clarence

Clyde Sr., Sarah Maude, Clyde Jr., Melody

Letter Exchange between Clyde Sr, Eugene Stoddard and Emily

regarding the children

June 6, 1949

Announcement to run for Mayor of Provo

June 4, 1951

Ordination Certificate to the Office of High Priest

September 15, 1953

Michael Weeks

January 1, 1954

Clyde & His Grandchildren

July 3, 1954

Clyde E Weeks, Sr.

September 22, 1955

Letter from Paris

May 28, 1958

Various Callings

![]()

June 1, 1958

Certificate of Bishop

July 7, 1958

Clyde &

Emily in Miami

July 7, 1958

Clyde Sr, Emily & Jerri Susan in 1958

November 8, 1962

Acknowledgement of Outstanding Service to Brigham Young

University

Clyde E Weeks, Sr - 1963

May 25, 1964

April 3, 1965

Clyde & Emily

Counselor in the Stake Presidency

May 28, 1969

Bishop Certificate

January 1, 1970

Clyde Everett Weeks, Sr

March 3, 1970

BR Michael, Clyde Jr., Sharee, Jerri Susan, Martin & Glen,

FR Karen, Emily, Clyde Sr & Myrna

April 4, 1970

Clyde

Jr, Michael, Clyde Sr, Martin & Glen

April 4, 1970

Clyde Everett Weeks Sr. Resume

May 5, 1970

Clyde E Weeks Sr

June 19, 1970

Glen & Diane's Wedding Reception

October 15, 1971

Retirement Letter to Dallin H. Oaks

October 27, 1971

Acceptance of Retirement from President Oaks

March 3, 1972

Clyde & Emily in Taiwan

November 20, 1972

Mission Call to Serve in England North Mission

June 8, 1973

Clyde & Emily in Cambridge England in 1973

June 5, 1975

Clyde E Weeks, Sr.

June 6, 1977

Clyde Sr, Clyde Jr, Skip (Clyde III), and Adam in 1977